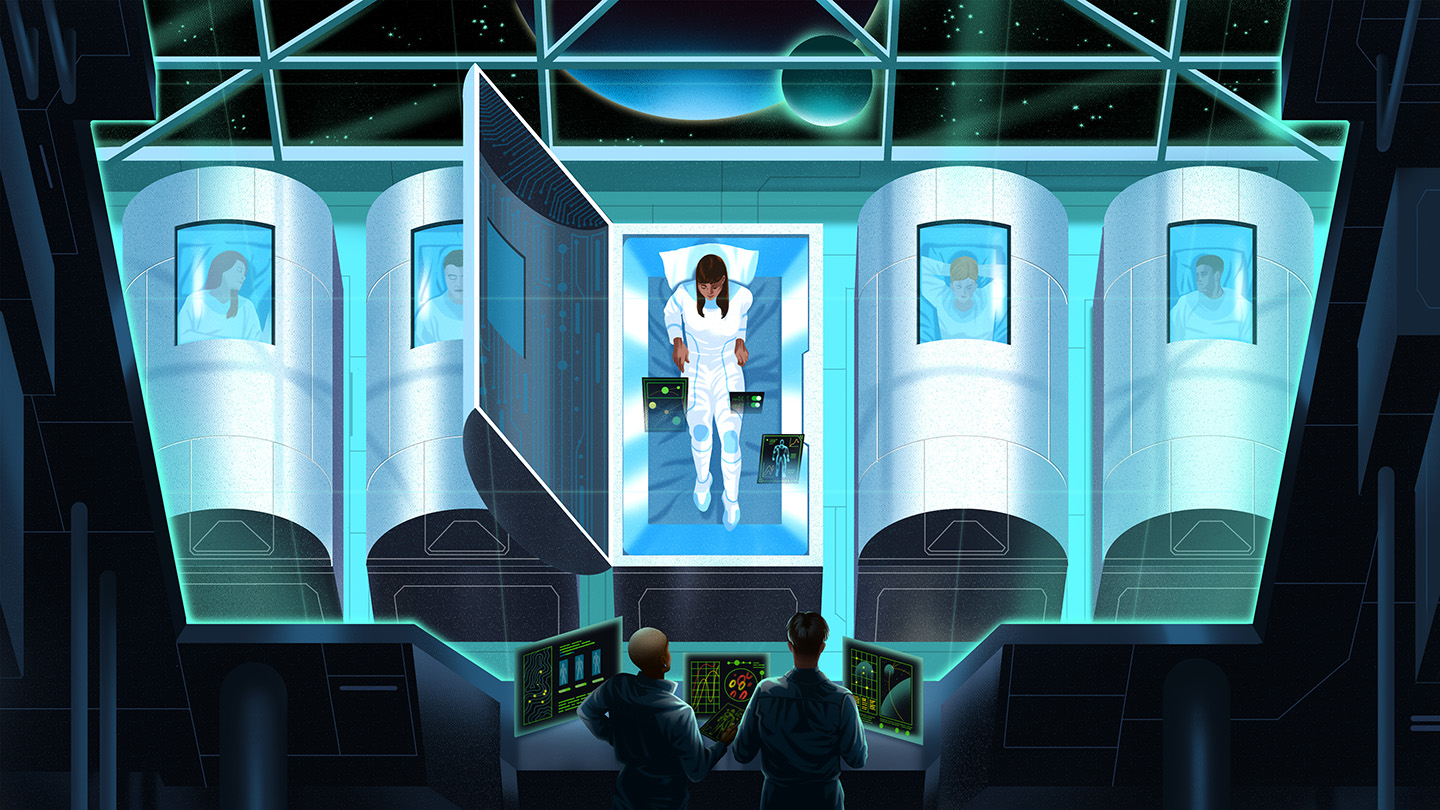

'Project Hail Mary' made us wonder how to survive a trip to interstellar space Skip to content Subscribe today Every print subscription comes with full digital access Subscribe Now Menu All Topics Health Humans Anthropology Health & Medicine Archaeology Psychology View All Life Animals Plants Ecosystems Paleontology Neuroscience Genetics Microbes View All Earth Agriculture Climate Oceans Environment View All Physics Materials Science Quantum Physics Particle Physics View All Space Astronomy Planetary Science Cosmology View All Magazine Menu All Stories Multimedia Reviews Puzzles Collections Educator Portal Century of Science Unsung characters Coronavirus Outbreak Newsletters Investors Lab About SN Explores Our Store SIGN IN Donate Home INDEPENDENT JOURNALISM SINCE 1921 SIGN IN Search Open search Close search Home INDEPENDENT JOURNALISM SINCE 1921 All Topics Earth Agriculture Climate Oceans Environment Humans Anthropology Health & Medicine Archaeology Psychology Life Animals Plants Ecosystems Paleontology Neuroscience Genetics Microbes Physics Materials Science Quantum Physics Particle Physics Space Astronomy Planetary Science Cosmology Tech Computing Artificial Intelligence Chemistry Math Science & Society All Topics Health Humans Humans Anthropology Health & Medicine Archaeology Psychology Recent posts in Humans Chemistry Machine learning streamlines the complexities of making better proteins By Skyler WareFebruary 19, 2026 Health & Medicine Home HPV tests won’t replace the ob-gyn By Jamie DucharmeFebruary 19, 2026 Artificial Intelligence Real-world medical questions stump AI chatbots By Tina Hesman SaeyFebruary 17, 2026 Life Life Animals Plants Ecosystems Paleontology Neuroscience Genetics Microbes Recent posts in Life Paleontology A mouth built for efficiency may have helped the earliest bird fly By Jay BennettFebruary 19, 2026 Animals Some dog breeds carry a higher risk of breathing problems By Jake BuehlerFebruary 18, 2026 Animals Regeneration of fins and limbs relies on a shared cellular playbook By Elizabeth PennisiFebruary 18, 2026 Earth Earth Agriculture Climate Oceans Environment Recent posts in Earth Climate Halting irreversible changes to Antarctica depends on choices made today By Carolyn Gramling9 hours ago Climate Snowball Earth might have had a dynamic climate and open seas By Michael MarshallFebruary 19, 2026 Oceans Evolution didn’t wait long after the dinosaurs died By Elie DolginFebruary 13, 2026 Physics Physics Materials Science Quantum Physics Particle Physics Recent posts in Physics Physics Physicists dream up ‘spacetime quasicrystals’ that could underpin the universe By Emily ConoverFebruary 17, 2026 Physics A precise proton measurement helps put a core theory of physics to the test By Emily ConoverFebruary 11, 2026 Physics The only U.S. particle collider shuts down – so a new one may rise By Emily ConoverFebruary 6, 2026 Space Space Astronomy Planetary Science Cosmology Recent posts in Space Astronomy This inside-out planetary system has astronomers scratching their heads By Adam MannFebruary 12, 2026 Space Artemis II is returning humans to the moon with science riding shotgun By Lisa GrossmanFebruary 4, 2026 Physics A Greek star catalog from the dawn of astronomy, revealed By Adam MannJanuary 30, 2026 Science & Society Project Hail Mary made us wonder how to survive a trip to interstellar space The fate of astronauts in Andy Weir’s book-turned-movie shows how risky that trip might be An astronaut emerges from human hibernation (center) while crewmates watch over those still in torpor. Glenn Harvey By Tina Hesman Saey 3 minutes ago Share this:Share Share via email (Opens in new window) Email Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit Share on X (Opens in new window) X Print (Opens in new window) Print Editor’s note: This story contains light spoilers for Project Hail Mary. I have long puzzled over something in Andy Weir’s 2021 book Project Hail Mary: Why did two of the three fictional astronauts die during an interstellar trip? It might be because Weir put his travelers into four-year-long medically induced comas, says Haig Aintablian, an emergency physician and flight surgeon who directs UCLA’s space medicine program. “How cool would it be if you went to sleep a few hours after launch, and you woke up right as you arrived on the planet or the celestial body that you’re approaching?” But, he says, “I don’t think keeping the human alive and in a comatose state is necessarily the best option.” Sign up for our newsletter We summarize the week's scientific breakthroughs every Thursday. After all, “the human body is not designed to just be a stagnant blob,” he says. Comatose astronauts would be in danger of deadly blood clots and debilitating muscle wasting from inaction. Infections stemming from tubes and devices required to keep a comatose person alive also would be risky. So, I wondered, what other ways might people survive interstellar travel? Frozen, Aintablian suggests. “When the day comes where you could freeze someone and just thaw them, you would have solved the issue,” he says. But the problem may be more than technological. No one knows if human bodies can withstand the physiological rigors of freezing and thawing the way wood frogs do. Human hearts don’t function well below about 28° Celsius, says integrative biologist Matthew Regan of the University of Montreal. Some people have survived deeper body temperature dips but only temporary ones, he says, not the years it would take to travel to a distant star. Maybe hibernating our way to the stars is the answer. Some small mammals that hibernate, like arctic ground squirrels, drop their body temperatures to below freezing during torpor, when the rodents’ metabolism drastically slows. “It’s 2 percent of what it usually is,” Regan says. “They’re just barely ticking over. It’s like pilot light levels.” Hibernating bears save less energy, dropping their body temperatures only a few degrees to 31° C or 32° C (around 88° to 90° Fahrenheit). Torpid animals are sedentary but they don’t develop blood clots and their muscles don’t atrophy, unlike bedridden humans. If humans could dial back our metabolism even a tad like bears do, space voyages would require fewer resources to keep the crew fed, healthy and happy. Torpor may even help protect against ionizing radiation, a big problem for space travelers, Regan says. But it probably wouldn’t be possible to snooze the whole trip. Every couple of weeks, ground squirrels and other hibernators rouse, rewarming their bodies and moving around. No one is sure why. It may promote muscle regeneration and help the brain stay healthy, says neurochemist Kelly Drew of the University of Alaska Fai

‘Project Hail Mary’ made us wonder how to survive a trip to interstellar space